How the ancient practice of Dream Yoga transforms sleep into a profound method for developing the enlightened mind

I’ll never forget the first time I became lucid in a dream and encountered what appeared to be a hostile figure. My initial reaction was the same as in waking life—fear, the impulse to run. But something shifted. I remembered I was dreaming, and with that recognition came a sudden curiosity: What if I approached this frightening being with compassion instead?

What happened next changed my understanding of Dream Yoga entirely. The figure didn’t disappear or transform into something benign. Instead, my own fear dissolved. I saw this “threatening” presence as it really was—a projection of my own mind, no more solid than morning mist. In that moment, I understood viscerally what my teachers had been pointing to: Dream Yoga isn’t just about having cool lucid dreams. It’s a direct path to developing bodhicitta, the awakened heart of compassion.

What Bodhicitta Actually Means (Beyond the Textbook Definition)

Most introductions to bodhicitta start with Sanskrit etymology and formal definitions. While that’s useful, it misses something essential. Bodhicitta is less like acquiring knowledge and more like falling in love—with all beings, with reality itself, with the possibility of freedom from suffering.

The Tibetan tradition describes two aspects of this awakened heart:

Relative bodhicitta is the aspiration and commitment to wake up fully so you can actually help others. Not in some abstract, eventually-when-I’m-enlightened way, but starting now. It’s the part of you that can’t turn away from suffering, that feels others’ pain as your own, that would give everything to ease the burden of just one being.

Absolute bodhicitta is harder to describe because it’s not conceptual. It’s the direct recognition that everything you take to be solid and real—including your sense of being a separate self—is more like a dream than you’ve ever imagined. And paradoxically, this recognition doesn’t make you care less about others. It makes you care more, because you see through the illusion of separation.

Here’s where Dream Yoga becomes interesting. Most practices cultivate these two aspects separately. You do compassion meditation for relative bodhicitta, then emptiness meditation for absolute bodhicitta. But dreams give you both at once.

“For the very instant that bodhicitta is born

In the weary captives enslaved within saṃsāra,

They are called heirs of the bliss-gone buddhas,

Honourable to gods, humans, and the world."

— Shantideva, Bodhicaryāvatāra (Chapter 1, Verse 10)

Why Dreams Are Different (And Why That Matters)

There’s a slogan in the Lojong mind training teachings: “Regard all dharmas as dreams.” When I first heard this, I thought it meant treating waking life as unimportant, like some kind of spiritual bypass. I was wrong.

The point isn’t that dreams and waking life are both unreal in a nihilistic sense. It’s that they’re both real in the same way—as appearances in consciousness that we habitually mistake for something more solid than they are.

Think about it. Last night you might have dreamed about an argument with someone. In the dream, your anger felt completely real. Your heart raced, your face flushed, you said things you regretted. The whole drama played out with convincing emotional weight. Then you woke up and realized none of it happened. The person you argued with was your own mind. The situation that upset you was your own mind. Even the “you” who got angry was your own mind.

Now here’s the uncomfortable question: How is today’s argument with your partner fundamentally different?

This isn’t philosophical speculation. It’s direct experience available every night. And once you start recognizing dreams as dreams while still in them, something remarkable happens. You begin to see the dream-like quality of waking experience too. Not as a belief, but as a lived reality.

The Subtle Body: Not as Esoteric as It Sounds

When I first encountered teachings on channels (tsa), winds (lung), and essence drops (tiglé), I’ll admit I was skeptical. It sounded like pre-scientific mysticism. But after years of practice, I’ve come to appreciate that the Tibetan medical and contemplative traditions are describing something real—even if the language is different from modern anatomy.

The subtle body maps aren’t trying to replace an understanding of neurons and neurotransmitters. They’re describing the energetic and experiential dimension of consciousness that Western medicine largely ignores. And for Dream Yoga, this matters enormously.

According to the tradition, during deep sleep the winds gather in the central channel at the heart. As you transition into dreaming, these winds activate the navel chakra. The clarity and stability of your dreams directly reflect the condition of your channels and the movement of your winds.

I’ve seen this play out in my own practice. When I’m stressed, eating poorly, or letting my daily practice slip, my dreams become chaotic, fragmented, hard to remember. When I maintain consistent practice—particularly purification methods like those taught in The Four Powers: Working with Past Negative Karma—my dreams become naturally more lucid, more stable, more workable.

This isn’t magic. You’re creating the conditions for awareness to remain continuous even as the gross conceptual mind shuts down for the night.

And this has everything to do with bodhicitta. When your channels are clogged with what the tradition calls karmic winds—essentially the energetic residue of habitual emotional patterns—genuine compassion struggles to arise. You might have the intention to care about others, but you’re too caught up in your own reactivity. Purifying the subtle body through dedicated practice removes these obstacles. It’s like clearing a channel so water can flow freely.

“In our busy lives we find it difficult to practice as much as we wish we could. Perhaps we meditate for an hour or two each day, but that leaves the other twenty-two hours in which to be distracted and tossed about on the waves of samsara. But there is always time for sleep; the third of our lives we spend sleeping can be used for practice."

— Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche

Tonglen in Dreams: Compassion Without Safety Rails

Tonglen—the practice of breathing in others’ suffering and breathing out relief—is one of the most powerful and challenging compassion practices I know. In waking meditation, I often notice myself pulling back, unwilling to fully take on the visualized suffering. There’s a self-protective impulse: “If I really let myself feel this, I’ll be overwhelmed.”

In dreams, that protective barrier thins dramatically.

I remember a dream where I encountered hundreds of beings in obvious distress. Instead of the usual dream response (confusion, trying to fix the situation, or waking up), I remembered to practice tonglen. I breathed in their suffering as thick, dark smoke. And because I was dreaming, the visualization happened effortlessly—no struggling to maintain the image, no wondering if I was doing it right.

What surprised me was the intensity. I could feel their pain, really feel it, in a way that’s harder to access in waking practice. And yet I wasn’t overwhelmed. Because it was a dream, I could see directly that the suffering, while feeling utterly real, had no solid substance. I could take it in completely without being destroyed by it.

Then I breathed out. In the dream, this emerged as radiant light that reached all those beings simultaneously. Impossible in waking life, natural in the dream. And as I practiced, something shifted. The boundary between “me” helping “them” started to dissolve. There was just the process itself—suffering being transmuted into relief, darkness becoming light.

This is what makes Dream Yoga such a powerful method for cultivating bodhicitta. You can practice compassion with an intensity and scope that’s simply not available in waking life, while simultaneously recognizing the empty, luminous nature of all experience.

When Nightmares Become Teachers

For years, I had a recurring nightmare about being chased. The pursuer changed—sometimes a person, sometimes an animal, sometimes just a presence—but the terror was consistent. Then one night, I became lucid in the middle of being chased.

Instead of using lucidity to escape or change the dream, I stopped running. I turned around.

The figure approaching me was dark and threatening. Everything in me wanted to flee or wake up. But I remembered a teaching from my lama about offering yourself completely, holding nothing back. So I stood there and thought, “Take whatever you want. My body, my life, everything. May it benefit you.”

The figure stopped. And in that moment, I recognized it—not as something external, but as my own fear given form. My own rejection of parts of myself. My own shadow, as Jung might say.

The nightmare didn’t transform into something pleasant. But my relationship to it changed completely. I felt a wave of compassion for this frightened, aggressive part of myself that I’d been running from for years.

This is advanced practice, and I’m not suggesting everyone should stay in nightmares without proper preparation. But it illustrates something important: every dream figure, every dream situation, is an opportunity to practice bodhicitta. Especially the difficult ones.

When you encounter hostility in a dream and respond with compassion instead of fear or aggression, you’re training the same neural pathways and mental habits you need in waking life. The person who cut you off in traffic, the family member who triggered you, the political figure whose views you despise—they all offer the same opportunity the nightmare figure offers: a chance to choose compassion over reactivity.

“In order to train in the path that would allow us to transform death, the intermediate state, and rebirth, we have to practice on three occasions: during the waking state, during the sleeping state, and during the death process."

— His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Sleeping, Dreaming, and Dying: An Exploration of Consciousness (Wisdom Publications, 1997)

The Moment Everything Changes: Recognizing the Dream

There’s a specific moment in becoming lucid that still, after years of practice, fills me with wonder. You’re in the middle of a dream—maybe flying, maybe in conversation, maybe in some bizarre situation—and suddenly you know: “This is a dream.”

Everything continues. The dream doesn’t stop. But your relationship to it transforms completely. Fear dissolves because you know nothing can really harm you. Grasping releases because you understand nothing here will last. And yet—and this is crucial—the dream remains vivid, engaging, meaningful.

This moment is a direct taste of absolute bodhicitta.

Gampopa, the great medieval Tibetan master, taught that recognizing the dream is essentially the same as recognizing the nature of mind itself. Both involve seeing through the apparent solidity of experience without denying that experience arises.

In lucid dreams, you can practice with this recognition in ways that are harder in waking life:

I might dissolve a dream object, watching it fade into space, then bring it back. The object was never truly there, yet it appeared. It was never truly gone, yet it disappeared. Emptiness and appearance, not contradictory but inseparable.

Or I’ll practice transforming my dream body—making it larger, smaller, multiplying it, changing its appearance entirely. Who am I if this body I take to be “me” is so malleable? What’s the solid self I defend and promote all day if it can shift so easily?

These aren’t just interesting experiences. They’re direct challenges to the cognitive habits that keep all beings trapped in suffering—the belief in solid, permanent, separate existence.

Practical Steps (Because Theory Isn’t Enough)

I’ve shared a lot of philosophical background, but let me get concrete. How do you actually practice Dream Yoga as a path to bodhicitta?

Before Sleep

This is more important than most people realize. The quality of your sleep and dreams is largely determined by how you prepare.

First, I review my day. Not with harsh judgment, but with honest reflection. Where did I help? Where did I harm? Where did I miss opportunities to show up with compassion? This isn’t about guilt—it’s about learning.

Then I set my intention for the night: “May my dreams serve the awakening of all beings. May whatever arises in sleep become an opportunity to practice compassion and wisdom.”

I spend a few minutes visualizing light at my heart center, with all beings resting there in peace. This plants seeds for both lucidity and compassion.

And I work with purification practices. I can’t overstate how much difference this makes. When I’m consistent with The Four Powers purification, my dreams are clearer, more stable, easier to work with. When I skip this preparation, I’m basically hoping for results without creating the conditions.

During Dreams

When you become lucid, the first task is stabilization. I look at my hands, touch objects, remind myself repeatedly “I’m dreaming.” Lucidity is fragile at first. Excitement can wake you up immediately.

Once stable, I remember bodhicitta. Sometimes I literally say in the dream, “I’m practicing for the benefit of all beings.”

Then I practice specifically based on what the dream offers:

If there are other beings in the dream, I practice tonglen with them. I might transform myself into a bodhisattva or healing deity and offer whatever they need.

If the dream is pleasant, I practice generosity—offering all this beauty and happiness to others.

If the dream is difficult, I practice patience and compassion toward whatever arises.

And throughout, I try to maintain awareness of the dream-like nature of it all. This isn’t solid reality, even though it feels that way. And neither is tomorrow.

After Waking

I used to just get up and start my day. Now I take a few moments to recall whatever dreams I can, not grasping at them but acknowledging them.

More importantly, I try to carry forward the recognition. If dreams are mind’s projection, is this waking day really so different? Can I maintain even a taste of that lucid awareness—knowing this is all appearance in consciousness, responding with compassion, not taking it all so seriously?

Then I dedicate whatever benefit came from the night’s practice to all beings. Nothing belongs to me alone.

What Actually Happens Over Time

I should be honest about expectations. Dream Yoga doesn’t produce instant results. I had maybe three lucid dreams in my first year of practice. Now, after many years, lucidity is fairly common. But it took time.

The tradition describes three stages:

Beginning: You achieve basic lucidity occasionally. The recognition “I’m dreaming” might last only a few seconds before you either wake up or fall back into ordinary dreaming. But even these brief moments start shifting something in your understanding.

Intermediate: Lucid dreams become more frequent and stable. You can maintain awareness for extended periods, transform dream content intentionally, and practice compassion within dreams with some consistency. Dream Yoga starts feeling like a genuine training ground.

Advanced: Awareness continues through sleep itself, not just dreams. The distinction between dream practice and waking practice dissolves. Bodhicitta becomes spontaneous, uncontrived, your natural way of being regardless of the state of consciousness.

I’m somewhere in the intermediate stage, and honestly, even here the benefits are profound. My reactivity has decreased significantly. When difficult situations arise, there’s more space, more choice in how to respond. And compassion feels less like something I have to generate and more like my baseline.

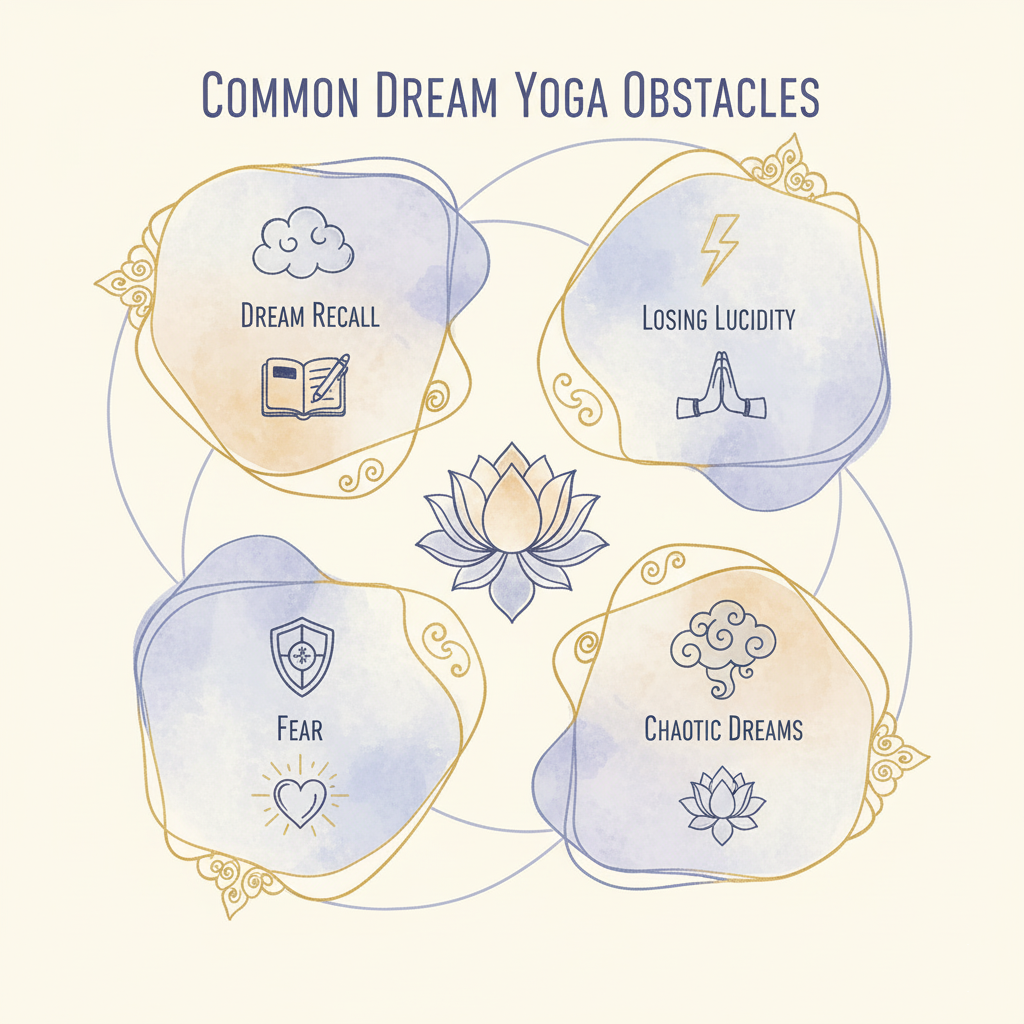

The Obstacles You’ll Actually Face

Dream recall: Most people start here. “I don’t remember my dreams, so how can I work with them?”

I struggled with this too. What helped: keeping a journal right by the bed and writing immediately upon waking, even if it’s just fragments. Setting clear intention before sleep. And—I keep mentioning this because it matters—working with purification practices that clear the subtle channels. When there’s less karmic obscuration, dreams naturally become clearer.

Losing lucidity immediately: You realize you’re dreaming, get excited, and boom—you’re awake.

The remedy is counterintuitive. When you become lucid, stay calm. Excitement is the enemy of stability. Some teachers recommend spinning in the dream or rubbing your hands together to stabilize. I find that touching objects and repeating “This is a dream” works well.

Chaotic, disturbing dreams: Sometimes your dreams are so fragmented or unpleasant that practice seems impossible.

This often reflects deeper issues—stress, unprocessed emotions, karmic patterns that need addressing. The Four Powers purification practice specifically targets these obstacles. Think of it as cleaning the channels so the water of awareness can flow more clearly.

Fear of losing control: Especially for people who’ve never practiced lucid dreaming, there’s sometimes anxiety about manipulating dreams or losing the boundary between sleeping and waking.

I understand this concern, but it’s backwards. Dream Yoga increases awareness and spaciousness. You become more present, not less. You’re not losing control—you’re gaining conscious participation in a process that was previously unconscious.

Where Science and Ancient Wisdom Meet

I’m not a neuroscientist, but I find the research on lucid dreaming fascinating because it’s starting to validate things contemplatives have known for centuries.

Studies show that lucid dreaming activates the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain associated with self-awareness, metacognition, and executive function. Regular practice appears to strengthen these capacities even during waking life.

Other research demonstrates that the brain treats imagined actions similarly to performed actions, activating overlapping neural networks. This supports what the tradition has always taught: practicing compassion in dreams trains the same mental qualities you need when awake.

And work on the default mode network—active during rest and dreaming, involved in self-referential thinking—suggests that practices dissolving the sense of solid self might be working with this network in specific ways.

I find this convergence encouraging, but I don’t practice Dream Yoga because science validates it. I practice because it works, because it transforms how I relate to my own mind and to others, because after years of many different contemplative methods, this remains one of the most powerful for developing genuine bodhicitta.

Weaving It All Together

Dream Yoga doesn’t stand alone. It works best when integrated with other practices.

The Lojong slogans, for instance, become vivid in dreams. “Drive all blames into one”—recognizing self-grasping as the root problem—is obvious when you see your mind projecting the entire dream, including the “problems” you react to. “Be grateful to everyone” includes being grateful to nightmare figures who give you opportunities to practice patience and compassion.

The six perfections all translate into dream practice. Generosity: offer your dream body, your dream possessions, even the dream itself. Ethics: maintain wholesome intentions even when actions seem to have no consequences. Patience: stay present with nightmares. Diligence: practice consistently across all states. Concentration: develop one-pointed focus within dreams. Wisdom: recognize the empty nature of all dream phenomena.

And purification practices create the foundation for everything else. I keep coming back to this because I’ve seen the difference so clearly in my own practice and in others I’ve worked with. When the channels are clear, when karmic obscurations are being actively worked with, everything else becomes more accessible.

“For as long as space endures

And for as long as living beings remain,

Until then may I too abide

To dispel the misery of the world."

— Shantideva, Bodhicaryāvatāra (Chapter 10, Verse 55), translated by the Padmakara Translation Group (Shambhala Publications, 1997)

A Word About Lineage and Getting Lost

I need to be careful here. I’m sharing from my own experience and what I’ve learned from teachers, but I’m not a lineage holder or authorized teacher. Dream Yoga, especially the deeper practices, really benefits from proper transmission and guidance.

The Longchen Nyingthig tradition, which I’ve trained in, presents Dream Yoga within a complete framework that includes preliminary practices to prepare the ground, root practices that form the foundation, and completion stage practices that integrate everything. It’s not meant to be picked up from a blog post.

If this material resonates with you, I’d encourage you to:

- Find a qualified teacher in an authentic lineage. There are now many Tibetan lamas teaching in the West and online.

- Receive proper transmission and instruction. Some practices require specific empowerments.

- Build a consistent daily practice that includes both waking and sleeping periods.

- Work with foundational practices like The Four Powers to create proper conditions for advanced work.

Reading about Dream Yoga is not the same as practicing it. And practicing alone without guidance can lead to confusion or wasted effort. This is a path walked by millions of practitioners over centuries. You don’t need to figure it out yourself.

Why Any of This Matters

Let me come back to the heart of it. Why practice Dream Yoga? Why go through all this effort?

Because we sleep roughly a third of our lives. If you live to 75, that’s 25 years unconscious. What if that time could serve the awakening of compassion instead?

Every moment spent training the mind—whether awake or dreaming—is a moment developing the capacity to genuinely help others. When we recognize a dream as a dream, we weaken the cognitive habits that trap all beings in suffering. When we practice compassion toward dream beings, we strengthen the pathways of genuine empathy. When we realize the empty nature of experience, we move toward the freedom that allows truly beneficial action.

The measure of success in Dream Yoga isn’t how many lucid dreams you have or how long you can maintain awareness. It’s whether your practice translates into greater compassion, wisdom, and benefit for others in your waking life.

My teacher once told me, “The point is not to be a good meditator. The point is to be a good person.” Dream Yoga is training for that—for showing up in the world with less reactivity, more openness, genuine care for others’ welfare.

Closing Thoughts

Every night, we enter a realm where the impossible becomes possible, where the boundaries that seem so solid by day dissolve into fluid potential. What if we used this nightly miracle not for entertainment or escape, but for the most important work humans can do—cultivating genuine love and compassion for all beings?

That’s the invitation of Dream Yoga as a path to bodhicitta. Use every moment—waking and sleeping—in service of awakening. Recognize that the boundary between self and other, between possible and impossible, is more permeable than we’ve been taught to believe.

And most of all, understand that if waking life is as dreamlike as our sleeping dreams—not as some intellectual concept but as lived experience—then we have the capacity to transform it through awakened awareness. We can choose compassion over reactivity. We can see through the illusion of separation. We can dedicate our lives—all 24 hours of each day—to the benefit of others.

This isn’t fantasy. It’s the gradual dawning of bodhicitta itself—the awakened heart that knows no separation from any living thing, that cannot turn away from suffering, that works tirelessly for the freedom of all.

May your dreams become a vehicle for awakening. May your sleep become practice. May every moment of your life serve the great purpose of liberation for all beings.

Further Resources

Courses:

- The Four Powers: Working with Past Negative Karma - Foundation practices for channel purification and clear dreams

May all beings benefit from these teachings. May the dreamlike nature of reality dawn in our hearts. May bodhicitta arise and never decline.

🙏